Egypt at a crossroads: The Arab world watches to take a cue from its biggest nation

Egyptian Coptic Christians chant angry slogans as they protest the recent attacks on Christians and churches, in front of the state television building in Cairo, Egypt. (File Photo)

Two key events have this week put post-revolutionary Egypt at a crossroads. How Egypt moves forward is certain to impact the course of popular revolts across the Middle East and North Africa.

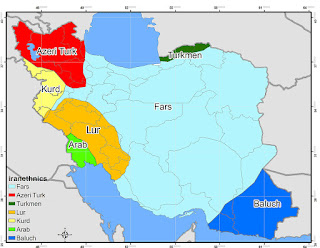

At stake are the fate of toppled autocratic leaders and the future of minorities in a world that constitutes a mosaic of ethnic and religious groups whose rights were often trampled on.

Both embattled Arab leaders and anti-government protesters will monitor closely the fate of ousted Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak who on Wednesday inched closer to facing corruption and other charges as well as how Egypt confronts mounting sectarian violence in the country.

At stake are the fate of toppled autocratic leaders and the future of minorities in a world that constitutes a mosaic of ethnic and religious groups whose rights were often trampled on.

Both embattled Arab leaders and anti-government protesters will monitor closely the fate of ousted Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak who on Wednesday inched closer to facing corruption and other charges as well as how Egypt confronts mounting sectarian violence in the country.

Mr. Mubarak’s face was thrown into sharp relief in a decision by newly appointed Egyptian Chief Coroner Kamil Ihsan Georgy that the former president had sufficiently recovered from a heart attack he suffered last month to be transferred from a hospital in the luxury Sinai resort town of Sharm el-Sheikh to Cairo’s infamous Tora Prison. During his 30-year presidency, Mr. Mubarak dispatched many political foes to the prison. Many are still there; others are no longer in a position to be released.

The decision is a dream come true for many Egyptians and something protesters elsewhere want to see happen in their own countries. Mr. Mubarak will join his sons Gamal and Ala’a who have been held in Tora for the past month as soon as the necessary medical monitoring equipment has been installed.

The expected transfer increases the likelihood that Egypt’s post revolution military rulers will put Mr. Mubarak on trial on charges of illegally amassing a fortune and responsibility for the deaths of hundreds killed in the protests that toppled Mr. Mubarak in February.

The transfer of the 81-year-old Mr. Mubarak to Tora Prison and the specter of his standing trial is certain to harden the battle lines across the Middle East and North Africa where some Arab leaders are battling mass demonstrations to hold on to power and others are maneuvering to prevent the eruption of protests.

The image of one of their own being incarcerated in the very prison where he once imprisoned his opponents will strengthen the resolve of embattled Arab heads of government like Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh who have employed brute force in so far unsuccessful attempts to quell protests.

Mr. Saleh demanded immunity from prosecution for himself and his family in failed negotiations to end the three month-old crisis in Yemen, where protesters are demanding his immediate resignation. Syrian forces shelled on Wednesday a neighborhood in Homs, the country’s third largest city, in a bid to crush the revolt against Mr. Assad’s regime.

The prospect of an Arab leader being put in the docket reportedly prompted some Arab countries to offer Egypt substantial aid in exchange for the dropping of all charges against Mr. Mubarak. The failed attempt to dissuade Egypt’s rulers from putting Mr. Mubarak on trial could also make some Arab leaders, should the protests spread to their country, more reluctant to respond with naked force.

That realization will not be lost on protesters whose perseverance in defying brutal government crackdowns is likely to be boosted by Mr. Mubarak’s transfer to prison.

Similarly, Mr. Mubarak’s transfer could also provide one more incentive for protests in Arab countries where discontent is widespread but has yet to erupt in public protests.

If Mr. Mubarak’s incarceration is likely to constitute a watershed, so is the way post-revolution Egypt deals with spiraling sectarian violence between Muslims and Christians. Egypt this week experienced its worst sectarian violence with the burning of two churches and clashes in the lower class Cairo suburb of Imbaba between Christians and Salafis–Muslims who want society to emulate the time of the Prophet Mohammed–that left 12 people dead and 230 others injured.

The violence spotlights the difficulty of transitioning from an autocratic regime that employed religion to bolster its grip to more liberal societies that embrace pluralism.

The inter-faith clashes together with mounting soccer violence in the last two months has further focused attention on the security vacuum that has existed in Egypt since Mr. Mubarak’s ouster as well as in Tunisia where protesters forced President Zine Abedine Ben Ali to resign in January.

Police in both countries have largely been publicly absent in a bid to shore up their image tarnished by the brutality they employed as henchmen of the toppled regimes of Messrs. Mubarak and Ben Ali. The police hope that their absence will avoid clashes that would only further damage their image and that public opinion will ultimately recognize that they are needed to maintain law and order.

However, for Mr. Mubarak’s successors to return Egypt to its historic role as a leader in the Arab world, they will have to not only fill the security vacuum created by the police’s absence, but also take a lead in creating a pluralistic society by ending decades-old discrimination against minorities. This week’s sectarian violence is a far cry from the momentous moments in Cairo’s Tahrir Square where Muslims and Christians joined hands in their opposition to Mr. Mubarak and Muslims protected Christians as they prayed.

A litmus test of whether a truly new, more liberal and more pluralistic Egypt will emerge from the ashes of the Mubarak regime will be the government’s willingness to legally enshrine the rights of Copts, who account for 10 percent of the population, and the forcefulness with which the government seeks to punish the perpetrators of this week’s violence.

Failure to do so could jeopardize the very goals of the popular revolt that put Egypt at the forefront of the struggle for change in the Middle East and North Africa; it would undermine efforts to restore regional Egyptian leadership and allow authoritarian leaders to use the specter of sectarian violence to justify repressive measures designed to prevent the anti-government protests from expanding.

That is hardly the legacy Egypt’s military rulers envision as they lead the country toward parliamentary and presidential elections later this year.

The decision is a dream come true for many Egyptians and something protesters elsewhere want to see happen in their own countries. Mr. Mubarak will join his sons Gamal and Ala’a who have been held in Tora for the past month as soon as the necessary medical monitoring equipment has been installed.

The expected transfer increases the likelihood that Egypt’s post revolution military rulers will put Mr. Mubarak on trial on charges of illegally amassing a fortune and responsibility for the deaths of hundreds killed in the protests that toppled Mr. Mubarak in February.

The transfer of the 81-year-old Mr. Mubarak to Tora Prison and the specter of his standing trial is certain to harden the battle lines across the Middle East and North Africa where some Arab leaders are battling mass demonstrations to hold on to power and others are maneuvering to prevent the eruption of protests.

The image of one of their own being incarcerated in the very prison where he once imprisoned his opponents will strengthen the resolve of embattled Arab heads of government like Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh who have employed brute force in so far unsuccessful attempts to quell protests.

Mr. Saleh demanded immunity from prosecution for himself and his family in failed negotiations to end the three month-old crisis in Yemen, where protesters are demanding his immediate resignation. Syrian forces shelled on Wednesday a neighborhood in Homs, the country’s third largest city, in a bid to crush the revolt against Mr. Assad’s regime.

The prospect of an Arab leader being put in the docket reportedly prompted some Arab countries to offer Egypt substantial aid in exchange for the dropping of all charges against Mr. Mubarak. The failed attempt to dissuade Egypt’s rulers from putting Mr. Mubarak on trial could also make some Arab leaders, should the protests spread to their country, more reluctant to respond with naked force.

That realization will not be lost on protesters whose perseverance in defying brutal government crackdowns is likely to be boosted by Mr. Mubarak’s transfer to prison.

Similarly, Mr. Mubarak’s transfer could also provide one more incentive for protests in Arab countries where discontent is widespread but has yet to erupt in public protests.

If Mr. Mubarak’s incarceration is likely to constitute a watershed, so is the way post-revolution Egypt deals with spiraling sectarian violence between Muslims and Christians. Egypt this week experienced its worst sectarian violence with the burning of two churches and clashes in the lower class Cairo suburb of Imbaba between Christians and Salafis–Muslims who want society to emulate the time of the Prophet Mohammed–that left 12 people dead and 230 others injured.

The violence spotlights the difficulty of transitioning from an autocratic regime that employed religion to bolster its grip to more liberal societies that embrace pluralism.

The inter-faith clashes together with mounting soccer violence in the last two months has further focused attention on the security vacuum that has existed in Egypt since Mr. Mubarak’s ouster as well as in Tunisia where protesters forced President Zine Abedine Ben Ali to resign in January.

Police in both countries have largely been publicly absent in a bid to shore up their image tarnished by the brutality they employed as henchmen of the toppled regimes of Messrs. Mubarak and Ben Ali. The police hope that their absence will avoid clashes that would only further damage their image and that public opinion will ultimately recognize that they are needed to maintain law and order.

However, for Mr. Mubarak’s successors to return Egypt to its historic role as a leader in the Arab world, they will have to not only fill the security vacuum created by the police’s absence, but also take a lead in creating a pluralistic society by ending decades-old discrimination against minorities. This week’s sectarian violence is a far cry from the momentous moments in Cairo’s Tahrir Square where Muslims and Christians joined hands in their opposition to Mr. Mubarak and Muslims protected Christians as they prayed.

A litmus test of whether a truly new, more liberal and more pluralistic Egypt will emerge from the ashes of the Mubarak regime will be the government’s willingness to legally enshrine the rights of Copts, who account for 10 percent of the population, and the forcefulness with which the government seeks to punish the perpetrators of this week’s violence.

Failure to do so could jeopardize the very goals of the popular revolt that put Egypt at the forefront of the struggle for change in the Middle East and North Africa; it would undermine efforts to restore regional Egyptian leadership and allow authoritarian leaders to use the specter of sectarian violence to justify repressive measures designed to prevent the anti-government protests from expanding.

That is hardly the legacy Egypt’s military rulers envision as they lead the country toward parliamentary and presidential elections later this year.

Comments

Post a Comment